Every compliance audit I’ve been through follows the same script. Someone asks for evidence that policy X governs system Y. You dig through SharePoint, Confluence, or worse – someone’s inbox. You assemble a PDF. The auditor nods. Six months later, you do it again.

The information exists. It’s just trapped in formats that can’t answer questions.

Daniel Rothmann recently wrote about this gap and called it Company as Code. His observation: we version-control our infrastructure, our deployments, our policy-as-code rules, but not the organizational fabric that ties them together. Policies, roles, org units, compliance mappings – all of it lives in documents nobody can query. He proposes a custom DSL to fix this.

The diagnosis is right. But the prescription misses something: the tool already exists.

The traceability problem isn’t new

In automotive cybersecurity, traceability isn’t optional – it’s mandated. ISO 21434 requires you to trace threats to risks to requirements to mitigations to verification. A TARA produces dozens of interconnected artifacts. When an auditor asks “which security requirement mitigates threat T-042, and how is it verified?” you need an answer in seconds, not hours.

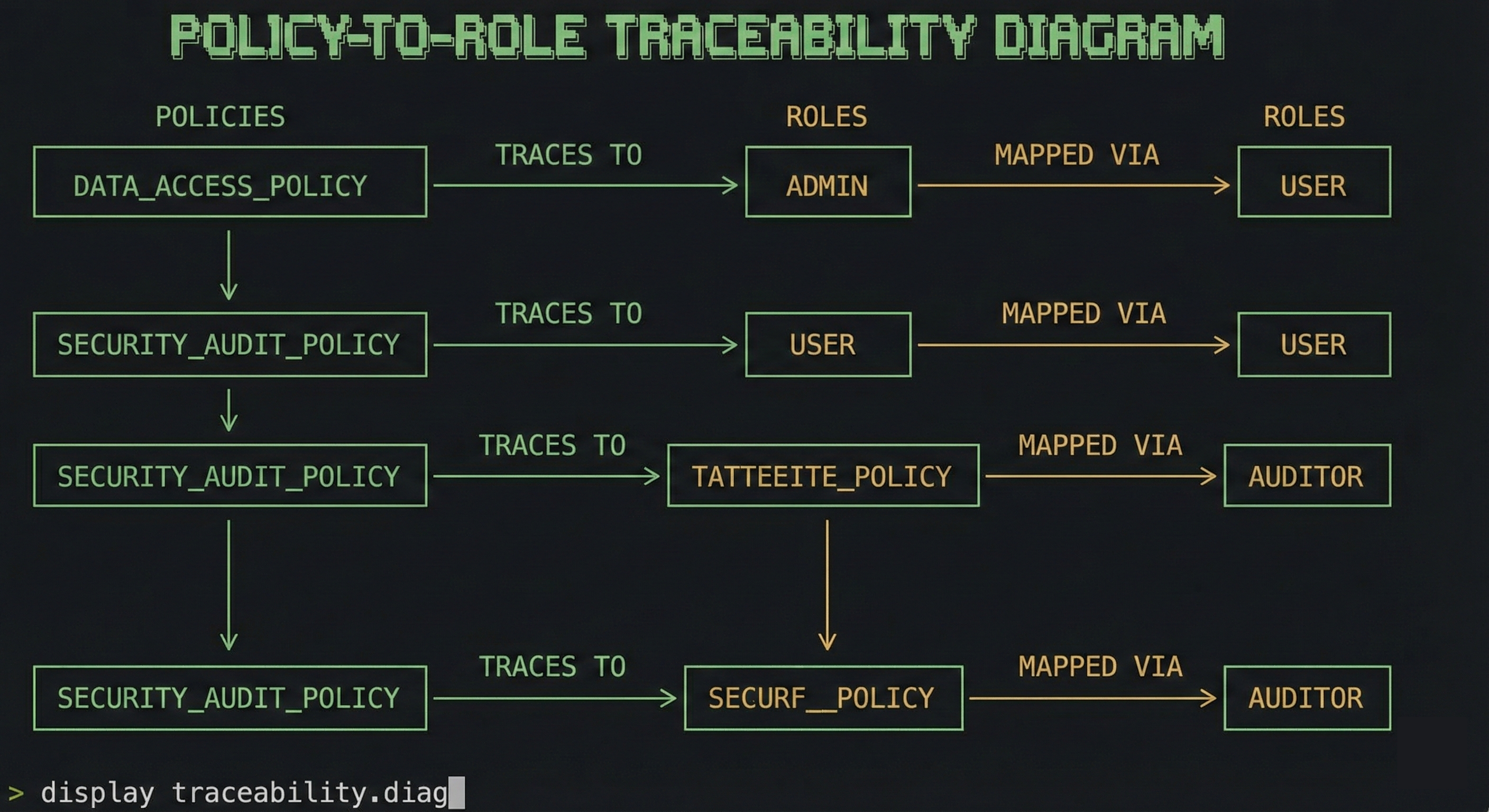

This is the same problem Rothmann describes at the organizational level. Policies reference roles. Roles are assigned to people. People operate systems. Systems must comply with external requirements. It’s a graph of relationships, and we store it in flat documents.

The compliance world already solved the traceability problem for requirements engineering. The tools exist. They just haven’t been pointed at organizational structure yet.

sphinx-needs already does this

Rothmann says a Company as Code system must be queryable, versionable, integrated, testable, and accessible. sphinx-needs checks four of those out of the gate.

Queryable. needtable and needfilter let you query across all defined objects by type, status, tags, or any custom field. “Show me all policies linked to role R_CISO” is a one-liner.

Versionable. It’s Sphinx. It lives in git. Every change to a policy, role, or org unit has a commit hash, a diff, and a blame.

Testable. This is where sphinx-needs goes beyond what Rothmann sketches. It doesn’t just let you run checks – it gives you schema validation, effectively strong typing for documentation. You define allowed statuses, enforce ID formats via regex, require explicit IDs, restrict tags, and set structural constraints through needs_warnings that fail the build when violated. A policy without an owner? Build fails. A role referencing a non-existent org unit? Build fails. Your CI pipeline doesn’t just gate code – it gates your organizational documentation with the same rigor. It’s type-checking for your company.

Accessible. It renders to HTML. Non-technical stakeholders read a website, not RST files.

The fifth – integrated – is where you’d need to extend. sphinx-needs won’t pull your org chart from Azure AD on its own. But its import/export mechanisms and needs.json give you the seams to build that.

What it looks like

Configuration lives in ubproject.toml. No Python. Just TOML. Your compliance team can read this.

# ubproject.toml

"$schema" = "https://ubcode.useblocks.com/ubproject.schema.json"

[project]

name = "ACME Corp - Company as Code"

description = "Organizational policies, roles, and compliance as code"

srcdir = "."

[needs]

id_required = true

id_regex = "[A-Z_]{2,10}(_[\d]{1,3})*"

extra_options = [

"owner",

"department",

"effective_date",

]

[[needs.types]]

directive = "role"

title = "Role"

prefix = "R_"

color = "#BFD8D2"

style = "actor"

[[needs.types]]

directive = "policy"

title = "Policy"

prefix = "P_"

color = "#DCB239"

style = "node"

[[needs.types]]

directive = "org"

title = "Org Unit"

prefix = "OU_"

color = "#9856a5"

style = "frame"

[[needs.extra_links]]

option = "governs"

outgoing = "governs"

incoming = "governed by"

[[needs.extra_links]]

option = "assigned_to"

outgoing = "assigned to"

incoming = "has role"

Then you define your organizational artifacts in RST, the same way you’d define requirements:

.. role:: Chief Information Security Officer

:id: R_CISO

:status: active

:assigned_to: OU_SECURITY

Responsible for information security strategy and compliance.

.. policy:: Data Retention Policy

:id: P_DATA_RET

:status: active

:governs: R_CISO

:owner: Legal Department

:effective_date: 2025-01-01

All customer data must be retained for 5 years and deleted

after the retention period unless legally required otherwise.

When the auditor shows up, you don’t dig through SharePoint. You query:

.. needtable::

:filter: type == 'policy' and 'R_CISO' in governs

:columns: id;title;status

:style: table

That’s it. A rendered table of every policy governing the CISO role, generated from source files your CI already validates.

Where it fits and where it stretches

sphinx-needs covers the documentation layer well. Your policies, roles, org units, and their relationships live in version-controlled RST files. Your CI validates them. Your auditor reads rendered HTML. That’s the 80% case.

But Rothmann’s vision goes further. He wants runtime integration – pulling org charts from Azure AD, syncing role assignments from HR systems, triggering Slack notifications when a policy changes. sphinx-needs wasn’t built for that. It’s a build-time tool, not a runtime platform.

Here’s where I’d draw the line: use sphinx-needs as the source of truth, not the integration bus. Export needs.json from your build. Let a separate pipeline sync that JSON against your actual systems. When Azure AD says someone holds the CISO role but your manifest doesn’t, that’s a drift alert – the same pattern GitOps uses for infrastructure.

You don’t need a custom DSL and a graph database and an event store on day one. You need a text file in git that your build system validates. Everything else is iteration.

Start with one commit

The best infrastructure-as-code tools didn’t start as grand platforms. Terraform started as a way to describe cloud resources in text files. Kubernetes manifests are just YAML. The power comes from the ecosystem that grows around a simple, correct primitive.

sphinx-needs is that primitive for documentation-as-code. Rothmann is right that Company as Code is the missing layer. But the answer isn’t to build something new from scratch. It’s to take a tool that already handles typed objects, traceability, schema validation, and queryable relationships – and point it at a new domain.

Start with one policy file. Link it to a role. Run the build. You just version-controlled your company.